Naval Warfare Of World War I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Naval warfare in World War I was mainly characterized by blockade. The Allied Powers, with their larger fleets and surrounding position, largely succeeded in their

When he became

When he became

Admiral Alfred Tirpitz had often visited Portsmouth as a naval cadet and admired and envied the Royal Navy. Like the Kaiser, Tirpitz believed Germany's future dominant role in the world depended on a powerful navy. He demanded large numbers of battleships. Even when ''Dreadnought'' was launched, making his previously constructed 15 battleships obsolete, he believed that eventually Germany's technological and industrial might would allow Germany to out-build Britain ship for ship. Using the threat of his own resignation he forced the Reichstag to build three dreadnoughts and a battle cruiser. He also put aside money for a future submarine branch. At the rate that Tirpitz insisted upon, Germany would have thirteen in 1912, to Britain's 16.

When this was leaked out to the British people in spring 1909, there was public outcry. The people demanded eight new battleships instead of the four the government had planned for that year. As

Admiral Alfred Tirpitz had often visited Portsmouth as a naval cadet and admired and envied the Royal Navy. Like the Kaiser, Tirpitz believed Germany's future dominant role in the world depended on a powerful navy. He demanded large numbers of battleships. Even when ''Dreadnought'' was launched, making his previously constructed 15 battleships obsolete, he believed that eventually Germany's technological and industrial might would allow Germany to out-build Britain ship for ship. Using the threat of his own resignation he forced the Reichstag to build three dreadnoughts and a battle cruiser. He also put aside money for a future submarine branch. At the rate that Tirpitz insisted upon, Germany would have thirteen in 1912, to Britain's 16.

When this was leaked out to the British people in spring 1909, there was public outcry. The people demanded eight new battleships instead of the four the government had planned for that year. As

While Germany was strangled by Britain's blockade, Britain, as an island nation, was heavily dependent on resources imported by sea. German submarines (

While Germany was strangled by Britain's blockade, Britain, as an island nation, was heavily dependent on resources imported by sea. German submarines (

excerpt and text search

* Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt and ''The military history of World War I: naval and overseas war, 1916–1918'' (1967) * Friedman, Norman. ''Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines, and ASW Weapons of All Nations: An Illustrated Directory'' (2011) * Halpern, Paul. ''A Naval History of World War I'' (1994), the standard scholarly surve

excerpt and text search

* Herwig, Holger H. ''Luxury Fleet: The Imperial German Navy, 1888–1918'' (1987) * Marder, Arthur. '' From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era'' (5 vol, 1970), vol 2–5 cover the First World War * Morison, Elting E. ''Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy'' (1942) * Stephenson, David. ''With our backs to the wall: Victory and defeat in 1918'' (2011) pp 311–49 * Terrain, J. ''Business in Great Waters: The U-Boat wars, 1916–1945'' (1999)

Naval Warfare

in

* Halpern, Paul G.

Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations

in

* Bönker, Dirk

Naval Race between Germany and Great Britain, 1898-1912

in

* Abbatiello, John

Atlantic U-boat Campaign

in

* Karau, Mark D.

Submarines and Submarine Warfare

in

* Miller B., Michael

Sea Transport and Supply

in

* ttp://www.worldwar1.co.uk/despatches.html Official Royal Navy despatches concerning notable engagementsbr>World's Navies in World War 1, Campaigns, Battles, Warship lossesGerman Naval Warfare – Room 40 Documents

{{Authority control

blockade of Germany

The Blockade of Germany, or the Blockade of Europe, occurred from 1914 to 1919. The prolonged naval blockade was conducted by the Allies of World War I, Allies during and after World War I in an effort to restrict the maritime supply of goods t ...

and the other Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, whilst the efforts of the Central Powers to break that blockade, or to establish an effective counterblockade with submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s and commerce raider

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

s, were eventually unsuccessful. Major fleet action

A fleet action is a naval engagement involving combat between forces that are larger than a squadron on either of the opposing sides. Fleet action is defined by combat and not just manoeuvring of the naval forces strategically, operationally or ...

s were extremely rare and proved less decisive.

Prelude

The naval arms race betweenBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

to build dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s in the early 20th century is the subject of a number of books. Germany's attempt to build a battleship fleet to match that of the United Kingdom, the dominant naval power of the 20th-century and an island country that depended on seaborne trade for survival, is often listed as a major reason for the enmity between those two countries that led the UK to enter World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. German leaders desired a navy in proportion to their military and economic strength that could free their overseas trade and colonial empire from dependence on Britain's good will, but such a fleet would inevitably threaten Britain's own trade and empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

.

Ever since the First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis or the Tangier Crisis was an international crisis between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. Germany wanted to challenge France's growing control over Morocco, aggravating France and Great Britain. The ...

(over the colonial status of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, between March 1905 and May 1906), there had been an arms race, involving their respective navies. However, events led up to this. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Power ...

was an American naval officer, extremely interested in British naval history. In 1887, he published ''The Influence of Sea Power upon History

''The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783'' is a history of naval warfare published in 1890 by the American naval officer and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan. It details the role of sea power during the seventeenth and eighteenth cent ...

''. The theme of this book was naval supremacy as the key to the modern world. His argument was that every nation that had ruled the waves, from Rome to Great Britain, had prospered and thrived, while those that lacked naval supremacy, such as Hannibal's Carthage or Napoleon's France, had not. Mahan hypothesized that what Britain had done in building a navy to control the world's sea lanes, others could also do - indeed, must do - if they were to keep up with the race for wealth and empire in the future.

Naval arms race

Mahan's thesis was highly influential and led to an explosion of new naval construction worldwide. The US Congress immediately ordered the building of three battleships (with a fourth, , to be built two years later). Japan, whose British-trained navy wiped out the Russian fleet at theBattle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (Japanese:対馬沖海戦, Tsushimaoki''-Kaisen'', russian: Цусимское сражение, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known as the Battle of Tsushima Strait and the Naval Battle of Sea of Japan (Japanese: 日 ...

, helped to reinforce the concept of naval power as the dominant factor in conflict. However, the book made the most impact in Germany. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

, had been much impressed by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, when he visited his grandmother, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

. His mother said that "Wilhelm's one idea is to have a Navy which shall be larger and stronger than the British navy". In 1898 came the first German Fleet Act, two years later a second doubled the number of ships to be built, to 19 battleships and 23 cruisers in the next 20 years. In another decade, Germany would go from a naval ranking lower than Austria to having the second largest battle fleet in the world. For the first time since Trafalgar Trafalgar most often refers to:

* Battle of Trafalgar (1805), fought near Cape Trafalgar, Spain

* Trafalgar Square, a public space and tourist attraction in London, England

It may also refer to:

Music

* ''Trafalgar'' (album), by the Bee Gees

Pl ...

, Britain had an aggressive and truly dangerous rival to worry about.

Mahan wrote in his book that not only world peace or the empire, but Britain's very survival depended on the Royal Navy ruling the waves. The Cambridge 1895 Latin essay prize was called "Britannici maris", or "British Sea Power". So when the great naval review of June 1897 for the Queen's diamond jubilee took place, it was in an atmosphere of unease and uncertainty. The question everyone wanted to know the answer to was how Britain was going to stay ahead. But Mahan could not give any answers. The man who thought he could was Jackie Fisher, commander in chief of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

. He believed there were "Five strategic keys to the empire and world economic system: Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boun ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, and the Straits of Dover." His job was to keep hold of all of them.

Fisher's reforms

When he became

When he became First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

, Fisher began drawing up plans for a naval war against Germany. "Germany keeps her whole fleet always concentrated within a few hours of England," he wrote to the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

in 1906. "We must therefore keep a fleet twice as powerful within a few hours of Germany." He therefore concentrated the bulk of the fleet in home waters, with a secondary concentration in the Mediterranean Fleet. He also had dozens of obsolete warships scrapped or hulked. The resources thus saved were directed to new designs of submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s, light cruisers

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

, battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s and dreadnoughts. Fisher proclaimed, "We shall have ten Dreadnoughts at sea before a single foreign Dreadnought is launched, and we have thirty percent more cruisers than Germany and France put together."

German response

Admiral Alfred Tirpitz had often visited Portsmouth as a naval cadet and admired and envied the Royal Navy. Like the Kaiser, Tirpitz believed Germany's future dominant role in the world depended on a powerful navy. He demanded large numbers of battleships. Even when ''Dreadnought'' was launched, making his previously constructed 15 battleships obsolete, he believed that eventually Germany's technological and industrial might would allow Germany to out-build Britain ship for ship. Using the threat of his own resignation he forced the Reichstag to build three dreadnoughts and a battle cruiser. He also put aside money for a future submarine branch. At the rate that Tirpitz insisted upon, Germany would have thirteen in 1912, to Britain's 16.

When this was leaked out to the British people in spring 1909, there was public outcry. The people demanded eight new battleships instead of the four the government had planned for that year. As

Admiral Alfred Tirpitz had often visited Portsmouth as a naval cadet and admired and envied the Royal Navy. Like the Kaiser, Tirpitz believed Germany's future dominant role in the world depended on a powerful navy. He demanded large numbers of battleships. Even when ''Dreadnought'' was launched, making his previously constructed 15 battleships obsolete, he believed that eventually Germany's technological and industrial might would allow Germany to out-build Britain ship for ship. Using the threat of his own resignation he forced the Reichstag to build three dreadnoughts and a battle cruiser. He also put aside money for a future submarine branch. At the rate that Tirpitz insisted upon, Germany would have thirteen in 1912, to Britain's 16.

When this was leaked out to the British people in spring 1909, there was public outcry. The people demanded eight new battleships instead of the four the government had planned for that year. As Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

put it, "The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight."http://www.historicgreenslopes.com/documents/Booklet_The%20Great%20War%20@%206%20Sep.pdf Tirpitz had no option but to consider Britain's new dreadnought-building program as a direct threat to Germany. He had to respond, raising the stakes further. However, the commitment of funds to out-build the Germans meant Britain was abandoning any notion of a two-power standard

The official history of the Royal Navy reached an important juncture in 1707, when the Act of Union merged the kingdoms of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain, following a century of personal union between the two countries. ...

for naval superiority. No amount of money would allow Britain to compete with Germany and Russia or the US, or even Italy. Thus a new policy, of dominance over the world's second leading sea power by a 60% margin, went into effect. Fisher's staff had been getting increasingly annoyed by the way he refused to tolerate any difference in opinion, and the eight dreadnought demand had been the last straw. Thus on January 25, 1910, Fisher left the admiralty. Shortly after Fisher's resignation, Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty. Under him, the race would continue; indeed Lloyd George nearly resigned when Churchill presented him with the naval budget of 1914 of 50 million pounds.

By the start of the war Germany had an impressive fleet both of capital ships and submarines. Other nations had smaller fleets, generally with a lower proportion of battleships and a larger proportion of smaller ships like destroyers and submarines. France, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Japan, and the United States all had modern fleets with at least some dreadnoughts and submarines.

Naval technology

Naval technology in World War I was dominated by the dreadnought battleship. Battleships were built along the dreadnought model, with several large turrets of equally sized big guns. In general terms, British ships had larger guns and were equipped and manned for quicker fire than their German counterparts. In contrast, the German ships had better optical equipment and rangefinding and were much better compartmentalized and able to deal with damage. The British also generally had poor propellant handling procedures, a point that was to have disastrous consequences for the British battlecruisers atJutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

.

Many of the individual parts of ships had recently improved dramatically. The introduction of the turbine

A turbine ( or ) (from the Greek , ''tyrbē'', or Latin ''turbo'', meaning vortex) is a rotary mechanical device that extracts energy from a fluid flow and converts it into useful work. The work produced by a turbine can be used for generating e ...

led to much higher performance, as well as freeing up room and thereby allowing for improved layouts. Whereas pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, prote ...

s were generally limited to , modern ships were capable of at least , and in the latest British classes, . The introduction of the gyroscope and centralized fire control, the "director" in British terms, led to dramatic improvements in gunnery. Ships built before 1900 had effective ranges of around , whereas the first "new" ships were good to at least , and modern designs to over .

One class of ship that appeared just before the war was the battlecruiser. There were two schools of thought on battlecruiser design: British and German. The British designs were armed like their heavier dreadnought cousins, but deliberately lacked armor to save weight in order to improve speed. The concept was that these ships would be able to outgun anything smaller than themselves, and get away from anything larger. The German designs opted to trade slightly smaller main armament (11 or 12 inch guns compared to 12 or 13.5 inch guns in their British rivals) for speed, while keeping relatively heavy armor. They could operate independently in the open ocean where their speed gave them room to maneuver, or, alternately, as a fast scouting force in front of a larger fleet action.

The torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

caused considerable worry for many naval planners. In theory, a large number of these inexpensive ships could attack in masses and overwhelm a dreadnought force. This led to the introduction of ships dedicated to keeping them away from the fleets, the "torpedo boat destroyers", or simply, "destroyers". Although the mass raid continued to be a possibility, another solution was found in the form of the submarine, increasingly in use. The submarine could approach underwater, safe from the guns of both the capital ships and the destroyers (although not for long), and fire a salvo as deadly as a torpedo boat's. Limited range and speed, especially underwater, made these weapons difficult to use tactically. Submarines were generally more effective in attacking poorly defended merchant ships than in fighting surface warships, though several small-to-medium British warships were lost to torpedoes launched from German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s.

Oil was just being introduced to replace coal, containing as much as 40% more energy per volume, extending range and further improving internal layout. Another advantage was that oil gave off considerably less smoke, making visual detection more difficult. This was generally mitigated by the small number of ships so equipped, generally operating in concert with coal-fired ships.

Radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

was in early use, with naval ships commonly equipped with radio telegraph, and merchant ships less so. Sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

was in its infancy by the end of the war.

Aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot air ...

was primarily focused on reconnaissance, with the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

being developed over the course of the war, and bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

aircraft capable of lifting only relatively light loads.

Naval mines

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any v ...

were also increasingly well developed. Defensive mines along coasts made it much more difficult for capital ships to get close enough to conduct coastal bombardment or support attacks. The first battleship sinking in the war — that of — was the result of her striking a naval mine on 27 October 1914. Suitably placed mines also served to restrict the freedom of movement of submarines.

Theaters

North Sea

The North Sea was the main theater of the war for surface action. TheBritish Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

took position against the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. Britain's larger fleet could maintain a blockade of Germany, cutting it off from overseas trade and resources. Germany's fleet remained mostly in harbor behind their screen of mines, occasionally attempting to lure the British fleet into battle (one of such attempts was the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

The Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, often referred to as the Lowestoft Raid, was a naval battle fought during the First World War between the German Empire and the British Empire in the North Sea.

The German fleet sent a battlecruise ...

) in the hopes of weakening them enough to break the blockade or allow the High Seas Fleet to attack British shipping and trade. Britain strove to maintain the blockade and, if possible, to damage the German fleet enough to remove the threat to the islands and free the Grand Fleet for use elsewhere. In 1918 the U.S. Navy with British help laid the North Sea Mine Barrage

The North Sea Mine Barrage, also known as the Northern Barrage, was a large minefield laid easterly from the Orkney Islands to Norway by the United States Navy (assisted by the Royal Navy) during World War I. The objective was to inhibit the m ...

designed to keep U-boats from slipping into the Atlantic.

Major battles included those at Heligoland Bight (in 1914

This year saw the beginning of what became known as World War I, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It als ...

and again in 1917), Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank (Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass ...

(in 1915), and Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

(1916). Though British tactical success remains a subject of historical debate, Britain accomplished its strategic objective of maintaining the blockade and keeping the main body of the High Seas Fleet in port for the vast majority of the war. The High Seas Fleet remained a threat as a fleet in being

In naval warfare, a "fleet in being" is a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the enemy's actions, but while ...

that forced Britain to retain a majority of its capital ships in the North Sea.

The set-piece battles and maneuvering have drawn historians' attention; however, it was the naval blockade of food and raw material imports into Germany which ultimately starved the German people and industries and contributed to Germany seeking the Armistice of 1918.

English Channel

Although the English Channel was of vital importance to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fighting in France, there were no big warships of the British Royal Navy in the channel. The primary threat to the British forces in the channel was the German High Seas Fleet based near Heligoland; the German fleet, if let out into the North Sea, could have destroyed any ship in the channel. The German High Seas Fleet could muster at least 13 dreadnoughts and many armored cruisers along with dozens of destroyers to attack the channel. The High Seas Fleet would be fighting against only six armored cruisers that were laid down in 1898–1899, far too old to accompany the big, fast dreadnoughts of the Grand Fleet based in Scapa Flow. The U-boat threat in the channel, although real, was not a significant worry to the Admiralty because they regarded submarines as useless. Even the German high command regarded the U-boats as "experimental vessels". Although the channel was a major artery of the BEF, it was never attacked directly by the High Seas Fleet.Atlantic

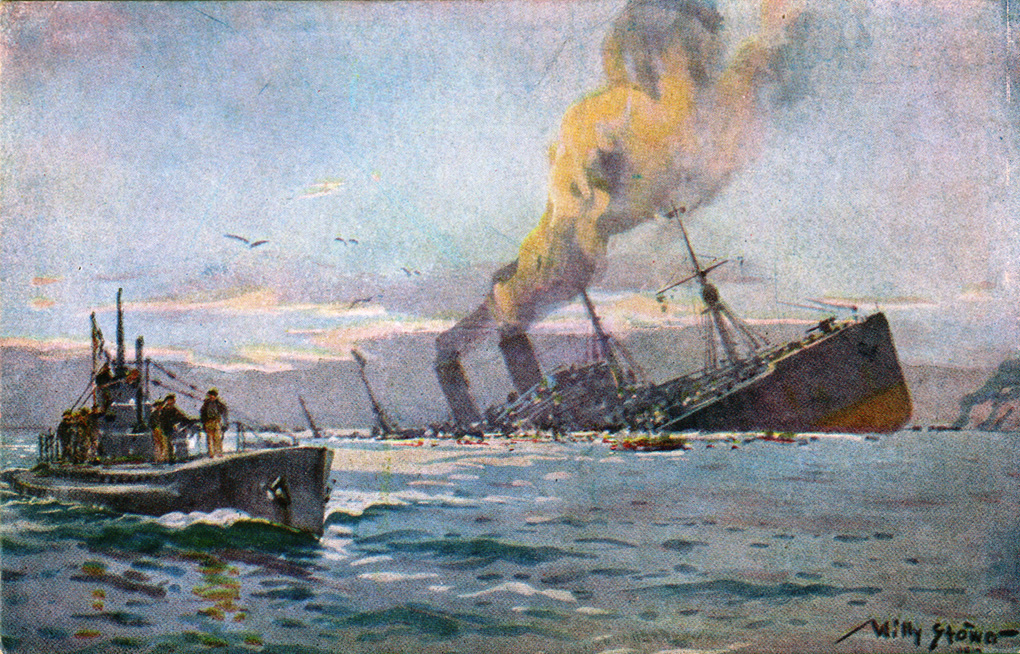

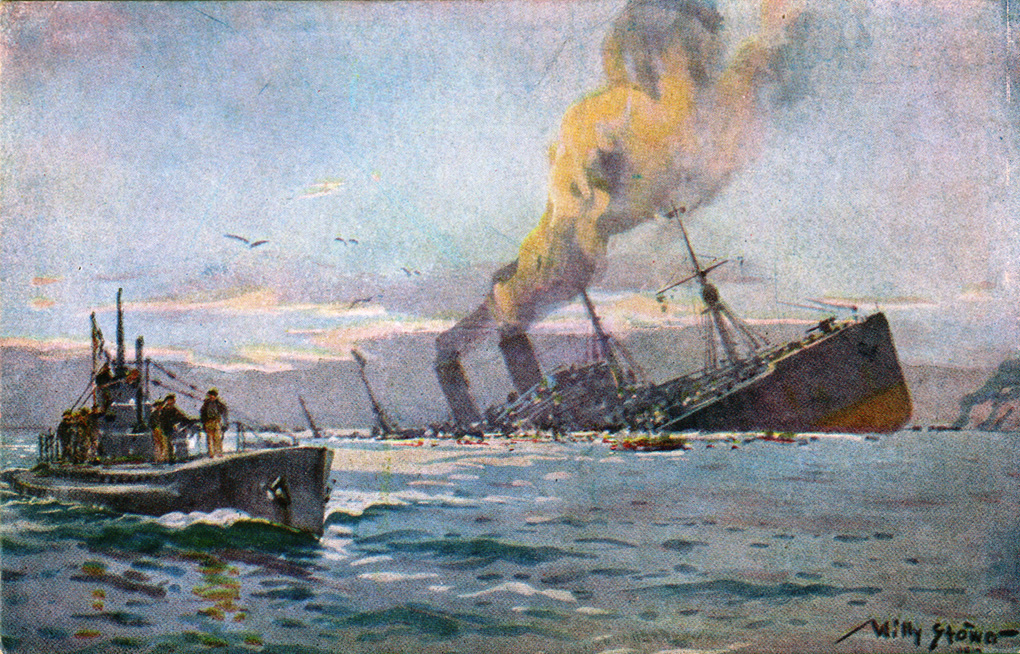

While Germany was strangled by Britain's blockade, Britain, as an island nation, was heavily dependent on resources imported by sea. German submarines (

While Germany was strangled by Britain's blockade, Britain, as an island nation, was heavily dependent on resources imported by sea. German submarines (U-boats

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare rol ...

) were of limited effectiveness against surface warships on their guard, but were greatly effective against merchant ships.

In 1915, Germany declared a naval blockade of Britain, to be enforced by its U-boats. The U-boats sank hundreds of Allied merchant ships. However, submarines normally attack by stealth. This made it difficult to give warning before attacking a merchant ship or to rescue survivors. This resulted in many civilian deaths, especially when passenger ships were sunk. It also violated the Prize Rules of the Hague Convention. Furthermore, the U-boats also sank neutral ships in the blockade area, either intentionally or because identification was difficult from underwater.

This turned neutral opinion against the Central Powers, as countries like the U.S. and Brazil suffered casualties and losses to trade.

In early 1917, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare, including attacks without warning against all ships in the "war zone", including neutrals. This was a major cause of U.S. declaration of war on Germany.

The U-boat campaign ultimately sank much of British merchant shipping and caused shortages of food and other necessities. The U-boats were eventually defeated by grouping merchant ships into defended convoys. This was also assisted by U.S. entry into the war and the increasing use of primitive sonar and aerial patrolling to detect and track submarines.

Mediterranean

Some limited sea combat took place between the navies of Austria-Hungary and Germany and the Allied navies of France, Britain, Italy and Japan. The navy of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

only sortied out of the Dardanelles once late in the war during the Battle of Imbros

The Battle of Imbros was a naval action that took place during the First World War. The battle occurred on 20 January 1918 when an Ottoman squadron engaged a flotilla of the British Royal Navy off the island of Imbros in the Aegean Sea. A lack ...

, preferring to focus its operations in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

.

The main fleet action was the Triple Entente attempt to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war by an attack on Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 1915. This attempt turned into the Battle of Gallipoli which resulted in a Triple Entente defeat.

For the rest of the war, naval action consisted almost entirely in submarine combat by the Austrians and Germans and blockade duty by the triple entente.

Black Sea

The Black Sea was mainly the domain of the Russians and the Ottoman Empire. The large Russian fleet was based inSevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

and it was led by two diligent commanders: Admiral Andrei Eberhardt

Andrei Avgustovich Ebergard (russian: Андрей Августович Эбергард; 9 November 1856 – 19 April 1919), better known as Andrei Eberhardt, was an admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy of German ancestry.

Biography

Eberhardt w ...

(1914–1916) and Admiral Alexander Kolchak

Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (russian: link=no, Александр Васильевич Колчак; – 7 February 1920) was an Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer who served in the Imperial Russian Navy and fought ...

(1916–1917). The Ottoman fleet on the other hand was in a period of transition with many obsolete ships. It had been expecting to receive two powerful dreadnoughts fitting out in Britain, but the UK seized the completed and with the outbreak of war with Germany and incorporated them into the Royal Navy.

The war in the Black Sea started when the Ottoman Fleet bombarded several Russian cities in October 1914. The most advanced ships in the Ottoman fleet consisted of two ships of the German Mediterranean Fleet: the powerful battlecruiser and the speedy light cruiser , both under the command of the skilled German Admiral Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the ''Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry o ...

. ''Goeben'' was a modern design, and with her well-drilled crew, could easily outfight or outrun any single ship in the Russian fleet. However, even though the opposing Russian battleships were slower, they were often able to amass in superior numbers to outgun ''Goeben'', forcing her to flee.

A continual series of cat and mouse operations ensued for the first two years with both sides' admirals trying to capitalize on their particular tactical strengths in a surprise ambush. Numerous battles between the fleets were fought in the initial years, and ''Goeben'' and Russian units were damaged on several occasions.

The Russian Black Sea fleet was mainly used to support General Nikolai Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolayevich Yudenich ( – 5 October 1933) was a commander of the Russian Imperial Army during World War I. He was a leader of the anti-communist White movement in Northwestern Russia during the Civil War.

Biography

Early life

Yuden ...

in his Caucasus Campaign

The Caucasus campaign comprised armed conflicts between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, later including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, the German Empire, the Central Caspian Dicta ...

. However, the appearance of ''Goeben'' could dramatically change the situation, so all activities, even shore bombardment, had to be conducted by almost the entire Russian Black Sea Fleet, since a smaller force could fall victim to ''Goeben''s speed and guns.

However, by 1916, this situation had swung in the Russians' favor – ''Goeben'' had been in constant service for the past two years. Due to a lack of facilities, the ship was not able to enter refit and began to suffer chronic engine breakdowns. Meanwhile, the Russian Navy had received the modern dreadnought which although slower, would be able to stand up to and outfight ''Goeben''. Although the two ships skirmished briefly, neither managed to capitalize on their tactical advantage and the battle ended with ''Goeben'' fleeing and ''Imperatritsa Mariya'' gamely trying to pursue. However, the Russian ship's arrival severely curtailed ''Goeben''s activities and so by this time, the Russian fleet had nearly complete control of the sea, exacerbated by the addition of another dreadnought, . German and Turkish light forces, however, continued to raid and harass Russian shipping until the end of the war in the east.

After Admiral Kolchak took command in August 1916, he planned to invigorate the Russian Black Seas Fleet with a series of aggressive actions. The Russian fleet mined the exit from the Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern T ...

, preventing nearly all Ottoman ships from entering the Black Sea. Later that year, the naval approaches to Varna, Bulgaria

Varna ( bg, Варна, ) is the third-largest List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, city in Bulgaria and the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and in the Northern Bulgaria region. Situated strategically in the ...

, were also mined. The greatest loss suffered by the Russian Black Sea fleet was the destruction of ''Imperatritsa Mariya'', which blew up in port on October 20 (October 7 o.s.) 1916, just one year after being commissioned. The subsequent investigation determined that the explosion was probably accidental, though sabotage could not be completely ruled out. The event shook Russian public opinion. The Russians continued work on two additional dreadnoughts under construction, and the balance of power remained in Russian hands until the collapse of Russian resistance in November 1917.

To support the Anglo-French attack on the Dardanelles, British, French and Australian submarines were sent into the Black Sea in the spring of 1915. A number of Turkish supply ships and warships were sunk, while several submarines were lost. The boats were withdrawn at the evacuation of the Dardanelles in January 1916.

The small Romanian Black Sea Fleet defended the port of Sulina

Sulina () is a town and free port in Tulcea County, Northern Dobruja, Romania, at the mouth of the Sulina branch of the Danube. It is the easternmost point of Romania.

History

During the mid-Byzantine period, Sulina was a small cove, and in t ...

throughout the second half of 1916, causing the sinking of one German submarine. Its minelayer also defended the Danube Delta from inland, leading to the sinking of one Austro-Hungarian Danube monitor. (See also Romanian Black Sea Fleet during World War I

During World War I, the Black Sea Fleet of the Romanian Navy fought against the Central Powers forces of the German Empire, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. The Romanian warships succeeded in defending the coast of the Danube Delta, corre ...

)

Despite losing most of their coastline to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

after the Second Battle of Cobadin

The Second Battle of Cobadin was a battle fought from 19 to 25 October 1916 between the Central Powers, chiefly the Bulgarian Third Army, and the Entente, represented by the Russo–Romanian Dobruja Army. The battle ended in a decisive victor ...

in October 1916, the Romanians still managed to keep the mouths of the Danube and the Danube Delta

The Danube Delta ( ro, Delta Dunării, ; uk, Дельта Дунаю, Deľta Dunaju, ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. The greater part of the Danube Delta lies in Ro ...

under their control, due to the combined actions of their riverine flotilla of four monitors and the protected cruiser '' Elisabeta'', based at Sulina. The Romanian Navy repelled two attacks of the Imperial German Navy on the port of Sulina. The first attack took place on 30 September 1916, when the Romanian torpedo boat '' Smeul'' engaged the German submarine '' UB-42'' near Sulina, damaging her periscope and conning tower and forcing her to retreat. The second attack took place on 7 November, when German Friedrichshafen FF.33 seaplanes bombarded Sulina but two of them were shot down into the sea by Romanian anti-aircraft defenses (including the cruiser ''Elisabeta'') and were subsequently captured by Romanian motorboats. In mid-November 1916, '' UC-15'', the only minelaying submarine of the Central Powers in the Black Sea,Marian Sârbu, ''Marina românâ în primul război mondial 1914-1918'', p. 68 (in Romanian) was sent to lay 12 mines off Sulina and never returned, being most likely sunk by her own mines along with all of her crew. She could have also been sunk by the barrage of 30 mines laid at Sulina by the Romanian minelayer ''Alexandru cel Bun''.

When Bulgaria entered World War I in 1915, its navy consisted mainly of a French-built torpedo gunboat called ''Nadezhda'' and six torpedo boats. It mostly engaged in mine warfare actions in the Black Sea against the Russian Black Sea Fleet and allowed the Germans to station two U-boats at Varna, one of which came under Bulgarian control in 1916 as '' Podvodnik No. 18''. Russian mines sank one Bulgarian torpedo boat and damaged one more during the war.

Baltic Sea

In theBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, Germany and Russia were the main combatants, with a number of British submarines sailing through the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

to assist the Russians. With the German fleet larger and more modern (many High Seas Fleet ships could easily be deployed to the Baltic when the North Sea was quiet), the Russians played a mainly defensive role, at most attacking convoys between Germany and Sweden.

A major coup for the Allied forces occurred on August 26, 1914 when as part of a reconnaissance squadron, the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

ran aground in heavy fog in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

. The other German ships tried to refloat her, but decided to scuttle her instead when they became aware of an approaching Russian intercept force. Russian Navy divers scoured the wreck and successfully recovered the German naval codebook

A codebook is a type of document used for gathering and storing cryptography codes. Originally codebooks were often literally , but today codebook is a byword for the complete record of a series of codes, regardless of physical format.

Crypto ...

which was later passed on to their British Allies and contributed immeasurably to Allied success in the North Sea.

With heavy defensive and offensive mining on both sides, fleets played a limited role in the Eastern Front. The Germans mounted major naval attacks on the Gulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia ( lv, Rīgas līcis, et, Liivi laht) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main con ...

, unsuccessfully in August 1915 and successfully in October 1917, when they occupied the islands in the Gulf and damaged Russian ships departing from the city of Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

, recently captured by Germany. This second operation culminated in the one major Baltic action, the battle of Moon Sound

The Battle of Moon Sound was a naval battle fought between the forces of the German Empire, and the then Russian Republic (and three British submarines) in the Baltic Sea during Operation Albion from 16 October 1917 until 3 November 1917 duri ...

at which the Russian battleship was sunk.

By March 1918, the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

made the Baltic a German lake, and German fleets transferred troops to support the White side in the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

and to occupy much of Russia, halting only when defeated in the west.

Other oceans

A number of German ships stationed overseas at the start of the war engaged in raiding operations in poorly defended seas, such as , which raided into theIndian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

, sinking or capturing thirty Allied merchant ships and warships, bombarding Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

and Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay ...

, and destroying a radio relay on the Cocos Islands

)

, anthem = "''Advance Australia Fair''"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = Australia on the globe (Cocos (Keeling) Islands special) (Southeast Asia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

, map_caption = ...

before being sunk there by . Better known was the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

, commanded by Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy in ...

, who sailed across the Pacific, raiding Papeete and winning the Battle of Coronel

The Battle of Coronel was a First World War Imperial German Navy victory over the Royal Navy on 1 November 1914, off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. The East Asia Squadron (''Ostasiengeschwader'' or ''Kreuzergeschwader'') ...

before being defeated and mostly destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands

The Battle of the Falkland Islands was a First World War naval action between the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy on 8 December 1914 in the South Atlantic. The British, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, sen ...

. The last remnants of Spee's squadron were interned at Chilean ports and destroyed at the Battle of Mas a Tierra

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

.

Allied naval forces captured many of the isolated German colonies, with Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

, Qingdao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

, German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

, Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

, and Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

falling in the first year of the war. As Austria-Hungary refused to withdraw its cruiser from the German naval base of Qingdao, Japan declared war in 1914 not only on Germany, but also on Austria-Hungary. The cruiser participated in the defense of Qingdao where it was sunk in November 1914.''A Brief History of the Austrian Navy'' by Wilhelm Donko pg. 79 Despite the loss of the last German cruiser in the Indian Ocean, , off the coast of German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozam ...

in July 1915, German East Africa held out in a long guerilla land campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

*Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* Bl ...

. British naval units despatched through Africa under Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson

Captain Geoffrey Basil Spicer-Simson DSO, RN (15 January 1876 – 29 January 1947) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the Mediterranean, Pacific and Home Fleets. He is most famous for his role as leader of a naval expedition to Lake Tanga ...

had won strategic control of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. ...

in a series of engagements by February 1916, though fighting on land in German East Africa continued until 1918.

Fleets overview

Allied Powers

Central Powers

Neutral powers

References

Further reading

* Benbow, Tim. ''Naval Warfare 1914–1918: From Coronel to the Atlantic and Zeebrugge'' (2012)excerpt and text search

* Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt and ''The military history of World War I: naval and overseas war, 1916–1918'' (1967) * Friedman, Norman. ''Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines, and ASW Weapons of All Nations: An Illustrated Directory'' (2011) * Halpern, Paul. ''A Naval History of World War I'' (1994), the standard scholarly surve

excerpt and text search

* Herwig, Holger H. ''Luxury Fleet: The Imperial German Navy, 1888–1918'' (1987) * Marder, Arthur. '' From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era'' (5 vol, 1970), vol 2–5 cover the First World War * Morison, Elting E. ''Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy'' (1942) * Stephenson, David. ''With our backs to the wall: Victory and defeat in 1918'' (2011) pp 311–49 * Terrain, J. ''Business in Great Waters: The U-Boat wars, 1916–1945'' (1999)

External links

* * Osborne, Eric W.Naval Warfare

in

* Halpern, Paul G.

Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations

in

* Bönker, Dirk

Naval Race between Germany and Great Britain, 1898-1912

in

* Abbatiello, John

Atlantic U-boat Campaign

in

* Karau, Mark D.

Submarines and Submarine Warfare

in

* Miller B., Michael

Sea Transport and Supply

in

* ttp://www.worldwar1.co.uk/despatches.html Official Royal Navy despatches concerning notable engagementsbr>World's Navies in World War 1, Campaigns, Battles, Warship losses

{{Authority control